Andrew Lewis Conn

|

Interview by Carl Marsh - June 2014

|

|

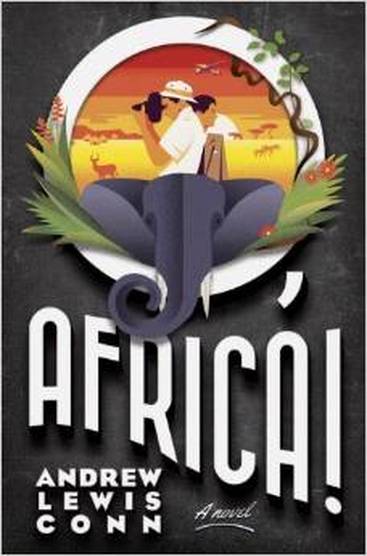

So Andrew, how did such a novel like O, Africa! come to be?

Similar to my experience writing P, my first novel, with O, Africa! I wanted to write a self-consciously big book—a big American book that grapples with big American themes. (At least for now, I’m a maximalist: the material’s got to be big enough, expansive enough, to sustain me over years and years while I’m working full-time.)The initial spark of inspiration for O, Africa! came in 2002 from reading an article by Michael Wolff in New York Magazine that mentioned a documentarian who was compiling the world’s largest video repository of September 11 footage. Wolff’s article had a one-sentence reference to the Korda brothers, “who in the early days of Hollywood created a bank of footage about the African bush that became the B-roll for every movie set in Africa.” It was just one line in the article, but I remember thinking, “Good Christ, there’s a big book in there!”. . . The early days of cinema and the birth of the movie industry. . . The first cameras rolling into Africa, the imposition of technology on the primitive. . . This is really rich stuff! Other tail winds and tea leaves began gathering: one of my favorite authors, Norman Mailer, once wrote, “minorities are the nervous system of America,” a great line with which I wholeheartedly agree. Also around that time I was hugely enamored with Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventure of Kavalier and Clay and thought a similar kind of book could be mounted that described the birth of the movies in America. So, I started thinking, instead of the Kordas—three Hungarian brothers who left Eastern Europe and co-founded London Films—how about twin American-Jewish brothers in New York who get entangled with a bunch of Harlem gangsters. . . Film and photography; the shift from a literary to a visual culture; how pop culture rolls over history; siblings/brothers; blacks, gays, and Jews inventing American culture in the early days of the 20th century. . . the themes kept snowballing and taking on mass. After being fortunate enough to get accepted into a couple of writers’ colonies, I began writing O, Africa! in February 2007. Now, the thing about starting a book—and most of my writer friends recount similar experiences—is that you do everything you can to push it down and away and not commit to the thing. Because writing it is going to be a huge pain in the ass: you’re going to live with years and years of uncertainty, your attention is always going to be half-way distracted, and it’s going to be hell on the people around you. The trigger moment—and, again, my fellow writers corroborate this—is that when the thing starts to organically take over, that is, when it becomes psychologically easier for you to just begin the damn thing rather than keep pushing the material down, that’s when you start. Another way of putting this: the only thing more miserable than a writer working on a book, is a writer not working on a book. Why was it important for you to tell this story? What do you hope readers will take away? It’s kind of a cliché, but we keep certain clichés around for good reason: you write the book you’d want to read. No one else was going to write O, Africa! so that mad dream fell to me. And then you freight the responsibility of telling that cockeyed story with all of the importance, enjoyment, fun, and torment that goes into bringing off a book. O, Africa! felt like a big story to me and a way of writing about America on a grand scale. One could make an argument that, along with jazz music, movies are our great indigenous art form. And a very interesting analogy could be made between the contradiction at the heart of America’s promise of itself (a country founded on the idea of freedom that practices slavery) and D.W. Griffith’ Birth of a Nation, which is at once the foundational text for commercial narrative cinema, a work of unprecedented artistic sophistication that is essentially the Rosetta Stone of movie grammar, and also a hateful and hidebound historic document. These are rich ideas, good material. Regarding the second part of the question: I hope O, Africa! entertains and surprises and delights people. I’m a novelist, not a polemicist, and I strongly believe that novels should help us ask better questions rather than presume to provide answers. Hopefully readers will let me know what they take away from the thing and those feelings and insights will entertain and surprise and delight me. Your protagonists, twin brothers Micah and Izzy Grand, couldn’t be any different from each other. What was your process for writing from the perspective of two distinct characters and for developing each of their unique voices? I liked the idea of having split protagonists who complement each other yet play off each other—and together form a kind of whole. I also love what I’ll call ying-yang movies, in which there are two characters, closer than brothers or lovers, who find themselves completing each other and, in some ways, serve as one character. Here I’m thinking of Scorsese’s Mean Streets, or David Cronenberg’s Dead Ringers, or Paul Thomas Anderson’s recent and almost wholly misunderstood and underestimated The Master. In terms of writing in character and developing distinct voices, I know some writers have described their experience of characters “taking over” when they are working on a book. While admitting that I’m indeed one of those authors who walks around mumbling dialogue to himself—I’d suggest that I’m writing a novel and not holding a séance. Meaning, the process of building a character for me is, I suspect, similar to a jazz musician taking flight or a good actor improvising in character: the craft and the structure allows you the room and flexibility to play. It’s the baseline technical requirements that provide for the sense of awakening and discovery. When creating a character, as an author, I need to determine what is the question that this character poses to the world? What is it that this character hopes to achieve (even if the character is in hiding from that realization)? And, then, as a corollary, is that question compelling enough to sustain the character across the length of a long narrative? At the most basic level, I think Izzy, the quieter, more introspective of my twin Grand moviemaking brothers, is trying to learn to be comfortable in his own skin as a gay man in 1920s America and feel worthy of love. It was more difficult for me to identify that loadstar question about Micah, who I always envisioned as something like a young Orson Welles-type figure who seems to have no trouble satisfying all of his rapacious urges. Ultimately, I think that Micah wants to know if he is capable of being a good man. Micah wants to reinvent himself as an artistic and romantic hero through the Africa experience and his relationship with his mistress Rose, an independent-minded light-skinned black woman, whom he finds himself deeply in love with despite himself. I have my own opinion on whether or not each brother achieves his goal, and will leave the rest to readers. Do you see any of yourself in the brothers? Yes. When I began O, Africa! I thought it would come as a relief to write something that was not contemporary or directly autobiographical. In the end, however, as a friend of mine put it, “there are method actors; and you’re a method writer. You pour yourself into your characters.” So, Micah is very much the boisterous side of my personality; Izzy the more quiet, introverted side, and the book, for all its plotting and period detail is, by default, intensely personal and emotionally autobiographical in ways that surprised me while writing it. Now, I’m going to make a comparison between what authors do and what actors do when it comes to building a character because the work is about understanding motivation and behavior, it’s just the tools that are different (words vs. voice, expression, and physical movement). And the method acting comparison is especially apt for this reason: no one watches Gangs of New York or There Will Be Blood and thinks, “Wow, that’s really terrible how Daniel Day-Lewis killed all those guys, especially because he seems like such a thoughtful, soft-spoken guy when accepting all those awards.” But almost everyone assumes that authors are guilty of practicing a personal kind of cannibalism whereby the writer him/herself and the people in his/her life become easily identifiable one-to-one analogues in their fiction. And it just ain’t so. Even if you set out to use, say, your father as the basis of a character in a book, by the time you got rolling with your narrative, the basic technical demands of the story—plotting, pacing, setting, suspense-building—means you’ll have to bend that image of your father to accommodate this fungible narrative construct. So, similar to method acting, sure you call upon memory and dream and lived experience, but then it becomes a matter of selection and amplification. (e.g., I’m sure the great Daniel Day-Lewis is as lovely a person as he projects, but there must be some seed of murderous rage in him that he is able to access, exploit, enhance, and deploy in those performances.) This is a long way of saying that I’d like to suggest that I spread myself out among all of my characters, and building and sustaining fictive creatures is always a matter of those four impulses: identification, selection, amplification, and imagination. Finally, regarding Izzy and Micah, the book is not incidentally dedicated to my sister, Jennifer. I don’t have a brother, but with the Grand boys I hoped to explore the sibling relationship. That relationship is an especially rich one, I think, because your brother or sister is in most cases the only peer who is with you for your entire life. And there’s the role siblings play as family fact checkers: yes, things were as good/weird/fucked-up as you remember. Your debut novel, P, was largely concerned with filmmaking and in O, Africa! you return to the world of film. In another life, would you have become a filmmaker? Movies were my first love; fiction the woman for whom I left my girlfriend to marry my wife. I studied film in college and have always felt I learn more about writing—about plot, dialogue, and character motivation—watching good actors in movies than from novels. (Like how the improvised scene in On the Waterfront with Marlon Brando picking up Eva Marie Saint’s dropped glove and putting it on his own hand teaches you all you need to know, really, about the meaning of subtext and how you might allow characters to turn psychology into behavior.) And it was a film critic, Pauline Kael—with her punchy, jazzed-up prose; that seductive, conspiratorial use of “we!”—who was the first writer I got really excited about. It was through reading The New Yorker critic’s reviews from out-of-print collections every lunch period in Stuyvesant High School’s library that I became aware of what it meant for an author to possess that mysterious thing called “voice.” I studied film in college and actually made a full-length movie in New York with a bunch of college students the summer I went from 19 to 20. (It was terrible.) After graduation, I wrote about films in publications including Film Comment and Time Out New York for many years, and worked in entertainment PR for about a dozen years. So, yes, my love of movies informs my writing and choice of subject matter. Thematically, O, Africa! is largely concerned with the moment when American culture began shifting from a literary one to an audio-visual one, and writing about that moment excited me a great deal. O, Africa! takes readers around the world—from the Coney Island boardwalk to the African bush—how did you choose your settings? And how did you so accurately capture such vastly different locales? That’s one of the great privileges you have as a writer: the ability to go anywhere and do anything. So, London, the African bush, early Hollywood, having a major character enter the book by way of Coney Island’s Wonder Wheel—yeah, sure, why not? I’m a proud Brooklyn native and Coney Island is one of my very favorite places. The opening set piece of the book, the filming of Quick Time in Coney Island, is based on Harold Lloyd’s Speedy from 1928, which features a cameo by Babe Ruth. I’ve long wanted to write about Coney Island, and both the amusement park’s historic position in American popular culture and how the movie industry finds its roots in a kind of carny/vaudeville tradition really made it the perfect setting for the novel’s opening. A big decision I needed to make in the early innings of the book had to do with whether or not I should set the Africa sections of the book in a real or imaginary country? Ultimately I landed on the side of, “Look, I’m not trying to write an anthropology textbook or a study of slavery.” In making this choice I had two great precedents in Saul Bellow’s Henderson The Rain King and John Updike’s The Coup. So, I decided to invent the country of Maliki, and to help tip off the reader, purposely set about making the village’s collection flora and fauna an impossible kind of Noah’s Ark. Other rationalizations for that very freeing early decision: I wanted the Africa sections of the book to progressively gain a kind of magic realist quality—and feared that if I began doing too much research, not only would it constrain my imagination, but I might end up losing two years! Finally, I justified my ignorance to a certain degree because the Grand Brothers know nothing about Africa before they set out on their adventure, which feeds one of the novel’s great themes: how popular culture has the ability to just steamroll facts and easily change collective perceptions of events of historic significance. The novel is also set in 1928. What was your research process like in terms of re-creating this world as it existed nearly 100 years ago? Having never written historical fiction before, something I grappled with in the early days of planning the book was this chicken-and-egg question: Does one spend years doing research and reach a kind of critical saturation point of confidence, or is it better to just plow ahead and figure out what you need to know as you go along? I was freelancing when I began the book, and one of my gigs was as a private tutor As part of the job I’d have to follow along with my students’ prep school curricula, which gave me an opportunity to revisit many of my favorite books from childhood. And the great lesson there—returning to works by the likes of Hemingway and Fitzgerald, 1920s novels that take place in the period O, Africa! describes—is an obvious one that’s still worth stating: good novels written from a given time don’t read like period pieces. In other words, Frederick doesn’t sidle up to Catherine and say, “Would you like a bite of this Clark Bar, the most popular candy bar in America in 1928, with sales of three-and-a-half million a year?” Re-reading those books was a revelation, freed me up from being overly bound by research, and made me realize that this kind of thing isn’t about seeding pages with hundreds of factoids— but instead being selective about seeding the one or two details that convince the reader you know what you’re talking about. There was some movie watching—Birth of a Nation, Speedy, and lots of Harold Lloyd to help build the Henry Till character—but probably a lot fewer silent films than readers might suspect. And inspiration, ideas, and imagery come from what might seem like unlikely places. Susan Sontag’s On Photography made a long and lasting impact on me, as did Walter Benjamin’s great essay, “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” I listen to music while I write and Arthur Marblestone’s entrance by way of the Wonder Wheel came to me from a very funny lyric from the song “Lo and Behold!” from Bob Dylan and the Band’s Basement Tapes.(“Now I come in on a Ferris wheel, and boys I sure was slick. . .”) The controversial German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl’s books of photographs chronicling her African expeditions seared their images into my brain. When you’re going full blast on a book, you find yourself pulling from everything around you. More than specific 1920s-related research, I was eager to find what felt to me like a big, period-appropriate voice that would sustain me over the length of writing the book. Part of finding that voice came with the decision to frame the book in the present tense—“he says,” “she goes,” etc.—an idea I lifted from John Updike’s Rabbit books. I used the strategy to bring things in the book closer and give them more urgency as I wrote it, and it worked. I never wanted O, Africa! to read like an Old Time-y nostalgia trip, and it didn’t feel that way as I wrote it. Finally, wise words from Philip Roth, who is a real Joe DiMaggio figure to me. Apropos his WWII alternate history novel, The Plot Against America, Roth described his writing strategy as “remember, don’t invent.” With O, Africa! I ultimately wasn’t trying to recreate accurately a world that existed in the 1920s; I was trying to faithfully capture and depict the people and places bumping around in my head. And if I could ask you what you favorite book is and why? I’d probably have to say Ulysses, corny or pretentious as that might sound. I was determined to write a novel upon graduating college. I meant to take an intensive Ulysses seminar during my senior year of college but couldn’t due to a scheduling conflict, so I began slowly making my way through the book (alongside annotations and guide books) on my own a year or two out of school. Reading Ulysses in this way was the great experience of my adult reading life, and sort of a shattering experience insofar as it changed my idea of what a novel could do. I felt that perhaps the most efficacious—perhaps only?—way of exorcising (and celebrating) that paralysis of influence would be to just take the thing on headfirst. I remember making the analogy to playing tennis with a player much, much better than you are: you go into the match knowing you will lose, but hoping you will emerge a better player for the experience. And so, my first novel, P, was this very screwy, contemporary riff on Ulysses, set in New York in the 1990s, starring a failed pornographer as the Bloom character and a ten-year-old girl genius as our modern-day Stephen Dedalus. What other titles go on that top shelf? Norman Mailer was a huge influence on me when I was a kid—I just loved the size of his ambition, and the notion that writing is tough work, it’s back work, it’s not (just) this effete, intellectual thing. Apart from John Updike’s Rabbit tetrology—another signal reading experience for me—I’m hard-pressed to name another book that tells us more about America than The Executioner’s Song. Philip Roth is another enormous influence: the way his work is both manic and controlled, comic and high-minded, colloquial but literary. My two favorite Roth books are probably The Counterlife—which shows how to do postmodernism right, without bells and whistles, and is the book where Nathan Zuckerman undergoes that seismic shift from being a mouth to being an ear—and Sabbath’s Theater, which is just stunning. The combination of real pornographic content (I mean, stuff that would make Alex Portnoy blush!) and the most profound meditations on family, memory, mortality, it’s like watching a gymnast execute a quadruple flip and land in a perfect split. Just impossible combinations of moves, and it remains, I think, Roth’s strangest and greatest achievement. (It’s no accident that book is the one he’s chosen to read from on his retirement tour.) What else? I probably learned more about a writer’s voice from the great film critic Pauline Kael than any novelist, so I’d throw her collection For Keeps into the mix. Lolita remains a continual source of renewal and inspiration and ravishment. The opening section of Don DeLillo’s Underworld might be our most perfect fifty pages of the last quarter century. You know, the usual suspects. . . What are or have you been reading at present? I was delighted to blurb Dustin Long’s excellent and lovely Bad Teeth. Griel Marcus’s collected essays on Bob Dylan and his monograph on “Like a Rolling Stone” represent some kind of high water mark of cultural criticism. Lawrence Osborne’s The Ballad of a Small Player reminded me of Graham Greene and Dostoevsky’s The Gambler in very good ways. Matthew Sharpe strikes me as one of America’s best and most underrated comic writers. And I recently was happy to discover the work of James Salter and Paula Vox. Most days, though, I hate to say it’s The New Yorker, New York Magazine, New York Times, and New York Review of Books on the treadmill. How did you get into writing? I was always sort of into writing, but film was really my first love. What happened was I was a dual film and English major in college, and the deeper I got into film production, the more I found that I wasn’t really cut out for it, and I much preferred the direct access of expression that fiction-writing provided. My first published pieces were film essays and freelance criticism, and there are things about film production I really love: the camaraderie of working with others, that sense of magic and discovery when a collaboration is really working, and how, at a student or semi-professional level filmmaking is really a cross between carpentry and art—there’s just an enormous component of physical labor involved that I found deeply satisfying. And I still love movies, and go all the time, and spend an inordinate amount thinking and talking about them. For all that, however, I have to agree with David Foster Wallace, who said during a Charlie Rose interview once something to the effect that a novel is still the best device that’s ever been created that teaches us what it means to be a fucking human being. That’s it: when I’m gone and someone wants to know what did this weird dude who lived in Brooklyn think about things like time and God and technology and sex and movies and America and working and family, they’ll be able to read these books and, if so inclined, have a pretty clear sense—not in a necessary immediate autobiographical sense, but still, as Martin Amis said, apropos of Lolita: “style is morality.” The deeper I get into fiction writing, and the more I learn about what goes into it and the pleasure one hopes to derive from it, I’ve come to think of it as a sense of total freedom. Apart from the aesthetic bliss of stringing together words and sentences and paragraphs; apart from the joy that comes with building characters that achieve a kind of psychological volume and can come to seem very real on the page, the truth is that you do it—or I do it—for the sense of freedom it provides. In other words, when I’m writing, I can go anywhere and do anything. I am ungovernable. I am answerable to no one. I am no longer my mother’s son. I am no longer my wife’s husband or my daughter’s father. I am no longer a Nice Jewish Boy From Brooklyn. I am no longer a Senior Vice President at a global communications company. Now, I also delight in being all of those things. So the balance of honoring those things while rejecting those things in order to create the work—because any work of art worth its salt exists as a statement of rejection of what’s come before; you will the thing into the world because you believe in its absence and need to exist—is a tricky thing. The psychology of writers is not the least complex thing in the world. . . And what tips would you offer to anyone wanting to write? Read widely. Choose toughing it out at a day job over an MFA degree. Surround yourself with a select group of good readers who will critique your work honestly and without agendas. Be ruthless with yourself. Do not make excuses. Get your ass in a chair. Keep it there. What are you currently working on or planning on doing in the next 12 months? I’m working on taking a nap. . . Beyond that, my third novel, The Dream Life of Corporations, aims to be a “Big Book About the Way We Live Now” in the tradition of Joseph Heller’s Something Happened, John Updike’s Rabbit tetralogy, and Jonathan Franzen’s achievement with The Corrections and Freedom. The inspiration for the book comes from several streams. The first is how, for nearly the past twenty years, I’ve made a living in New York working in public relations and corporate communications. That is, I’ve earned my daily bread for my entire adult life as a writer, but practicing a very specific kind of writing with very specific business objectives. Suffice to say, the subject of how language is deployed and manipulated in corporate communications work is exceedingly rich and fertile material for a fiction writer. Second, I’ve often thought about how my parents, who have been retired now for a number of years, stopped working just before the Internet, e-mail, and social media began to fundamentally change the nature of the workplace. If they were to be suddenly dropped into an office (regardless of business sector), they quite literally would not recognize or understand what work looks like today or the work product even is. The task of describing that phenomenon—how our work life has changed so dramatically in so relatively short a time; how most days are spent like the boy with his thumb in the dam, trying to close an endless series of communications loops; what the intrusion of mobile devices and 24/7 availability do to a person’s inner imaginative life and external family life—is, I believe, the responsibility of the novelist. Third, I want to task myself with writing a deeply Freudian novel. A dedicated Freudian, I believe that one’s dream life, one’s unconscious life, is absolutely as rich and varied and valid as one’s waking life. In many ways corporate life—in its insistence on the primacy of ego and persona—exists as the antithesis and denial of the unconscious. Per Freud, however, the unconscious always has its day, and so the collective dream life of the corporation always manages to break free in weird and untenable ways. (I work in crisis communications, and am reminded of Tony Hayward’s off-the-cuff remark during the height of the BP oil crisis: “I want my life back.”) The Dream Life of Corporations promises to be a book of visions, personas upended, and repression unleashed. Think David Lynch’s Blue Velvet set in a NYC office! There have been several good, worthy, recent books about the lower rungs of modern American office life (Joshua Ferris’s Then We Came to the End and Ed Park’s Personal Days immediately come to mind). I do not think, however, that a major novel has been written about the upper echelons of corporate life today, specifically about communications work, or that any recent novel of similar setting has attempted the kind of scope and richness of character I hope to achieve here. As I’ve pretty much just begun serious work on the new book, allow me to end this Q&A with a note about writerly ambition. You need to convince yourself at the outset that what you’re working on is unprecedented and of the first order of importance and will be the best thing you’ve ever done. Norman Mailer made a comparison once between writers of serious fiction and terrorists that at first glance sounds out-of-left-field and entirely unwholesome but is really quite astute. Novelists and terrorists are similar, Mailer proposed, because each spends his time working in secret for many years on some grand scheme, fueled with zealot-like conviction, driven forward by the belief that if he can bring off his plan he stands a chance of altering by a degree society and the collective unconscious. . . A strange tribe, writers! There was one last question that I have to ask every single person I interview, it's sort of my trademark. Would you be so kind as to tell me "If you could be an animal, what would it be, and why"? I've enjoyed this interview. . . So, I have some difficulty answering this question because I had pretty bad allergies growing up as a kid, and was born and raised in the city, so I had next to no experience with animals; subsequently, as an adult, I'm one of those people who will cross the street in order to avoid crossing paths with dogs on leashes, etc. A bunch of clichéd ways to answer this question might include: a lion or jaguar, because they're pretty cool and fast and fierce; or some kind of winged creature so you could fly around all day being free. . . We have a turtle, which is really a perfect city pet. And some of those guys last for a hundred years and seem pretty chilled out just walking slowly back-and-forth taking it all in. But I suppose I'd have to stick with the first animals that flashed into my head, which are dolphins. They're really beautiful, and really graceful, and really friendly, and apparently really smart, and they're faces at rest make enormous smiles, and there's really no arguing with that. Andrew |

Occupation: Author

Country: USA |